Exhaustibition: Performing wellness in the arts

As part of Next Wave’s Writers in Residence program, two physically disabled writers made a foolhardy decision to attend as many Next Wave exhibitions, performances and events in one weekend as possible – in an attempt to investigate issues of access and a culture of exhaustion in the arts.

Stepping out of the lifts and through West Space’s sliding glass doors, you immediately spot your own body – relieved of an arm, a pair of legs or your own head, depending on the angle you’re looking at Hany Armanious’ Body Swap (2015) from. A mirrored partition that functions as both a guillotine and Dr Frankenstein’s sewing kit.

Disorientated, you pass cinematic vignettes – a grotestque yet artfully sculpted bust (again, a body without a waist, without arms) and a shimmering gold dress high up a ladder that has misplaced the body wearing it entirely. For an unmedicated and well-rested mind, these disparate images might not have been so bewildering – we had no such luxury.

While this makes for an intense and exhausting exhibition experience, there is a silver lining. The haze of chronic pain and medication robs you of your critical (and perhaps sceptical) faculties, and makes for much more immediate and visceral experiences. It takes away your learned preconceptions – allowing the artist a much more direct route to your subconscious. In that way, the chronically exhausted might just make the perfect audience.

Passing through this collection of odd images that make up Next Wave’s The Fraud Complex – curated by collaborative duo Johnson+Thwaites – we were relieved to find the enclave dedicated to Katie West’s Decolonist had a place to sit, a window ledge lined with linen.

Decolonist offers a pocket of true serenity. Surrounded by fibre sculpture using native plants, you’re taken through a guided meditation that encourages visitors, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, to reflect on and release the past and continuing trauma of Australia’s colonisation. Making haste for the ledge we found that hidden beneath the linen were bundles of eucalyptus leaves. Our interaction with the space made the experience all the more fragrant, immersive; a direct consequence of our inability to stand for very long without pain.

The Fraud Complex and Decolonist were just 2 of a possible 37 exhibitions, performances and interactive experiences you could engage with across the course of 2016’s Next Wave Festival.

This might sound like a lot, but in the art world on any given week there are hundreds of exhibitions vying for your attention and a social assumption you will go – otherwise what will you talk about at the next exhibition? Dancing all night at Falls Festival, suffering from screen-induced headaches at Melbourne International Film Festival, braving the cold each night at MONA’s Dark MOFO: there is a specific, wilful imperviousness to exhaustion that is demanded from festival experiences and the arts community at large, along with a certain pride in endurance. Which is fine – if your life, body and mind enable that.

Now, there’s no particular need to get into the nitty-gritty of our own specific ailments, suffice to say we have one good leg between the both of us and are, sporadically and chronically, at the mercy of muscle fatigue, pain and drug-induced mental fogs. But this isn’t about us specifically, or even disabled people in general. We’re just a pair of guinea pigs with a lower-than-average threshold for exhaustion, and, as such, are perhaps more attuned to the various ways art and festival settings demand time and energy from all of us.

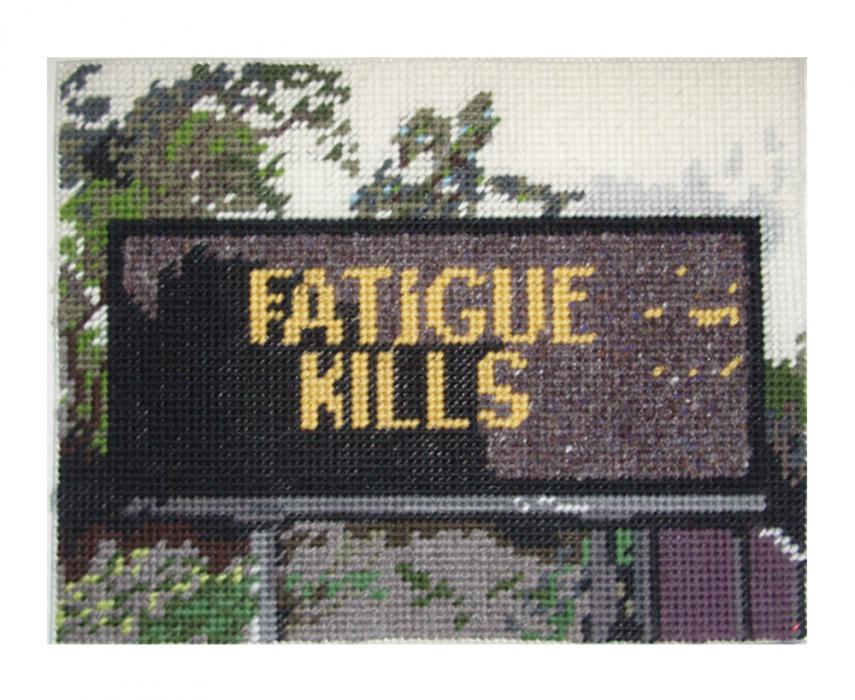

Michelle Hamer, known for her exquisite tapestry landscapes, understands all too well the struggles of performing wellness in the art world, that stem from making work, exhibiting it and networking, while managing a chronic condition.

“Most events are about facades. For me every opening, every event, every meeting, every conversation is a difficult choice… and that includes my own exhibitions. But having made the choice I am there to enjoy the façade for myself as much as possible. I am upright when my body hurts and wants to collapse. I am smiling, nodding and talking but I may not be easily connecting with what those conversations mean. I shift from one leg to the other, hoping that this will somehow relieve the strain. I have attempted to calculate the toll in advance to enjoy the moment. I have planned my week considering the event and any resultant recovery. So in that moment my appreciation of being out is real. The facade is masking how much planning, preparation and recovery is required for those few moments of enjoyment.”(1)

Going to every exhibition, event and evening is fine if your life enables that. But for many, their circumstances, schedules, mind and body don’t allow for that kind of commitment. Even for those whose circumstances enable such a lifestyle now, at any moment it could come crashing down. In this way, we are all acting out our own superficial narrative of wellness and constant productivity, ignoring the reality of burnout.

To quote writer Alison Croggon in a recent ArtsHub article: Burnout is an occupational hazard in the arts.(2)

It’s not just chronic conditions or disabilities which have this effect: a sudden injury at work, having children, economic pressures, even simple lack of sleep all take their toll.

Artist Eva Abbinga – who for Next Wave Festival constructed an intricate, 7 metre quilt that questioned our colonial past – is no stranger to this, grappling with a time consuming project amongst the all-encompassing demands of motherhood: “Festivals aren’t exactly life friendly”, in her own words.

Her quilted piece, Arrival of the Rajah, was first stop on the second day of our weekend exhaustibition marathon. Up a flight of stairs in one of Abbotsford Convent’s larger buildings, the quilt sat dead centre in an open, airy room. Recorded sounds of the ocean built a lurching, below-deck soundscape around us. It was a rich experience – but again, as Decolonist was, meditative. Serene.

As first order of the day, we managed to leave with some energy in our back pocket – but passing one of Abbotsford Convent’s wild and sweaty dance classes on our way out, we couldn’t help but dread the sweat that would go into checking off the remaining six exhibitions on the day’s agenda.

“But you don't have to go to so many exhibitions and events, to do so much!” we hear you cry. And that may be true – for casual exhibition attendees. Unfortunately, unlike other sectors where a clearer work/life balance is encouraged, fighting fatigue is a very real issue among art practitioners. In 2014, $68 million was cut from the Australia Council for the Arts, in favour of George Brandis’ “slush fund” Catalyst. Over the past few years the art world has witnessed the devastating repercussions of these cuts, with over 62 institutions no longer receiving Australia Council Funding.

In such a precarious climate, one never knows if each opportunity will be the last. With no standard living wage, artists often live and breathe their profession to get ahead in a highly competitive and overly saturated environment. Indeed, if there are no paid opportunities, young practitioners must ‘work for free’, proving to their peers they are capable. While some refuse to work under such conditions, there are always those that will, and these are the people that will ‘get ahead’ the fastest. This deeply problematic labour economy breeds a culture of exhaustion amongst art practitioners, alongside their viewers and patrons.

The arts demand full immersion, you live and breathe your practice rather than clocking in and out as with other professions. Art events are both professional and social, doubling the incentive to attend, and, accordingly, doubling the guilt you might feel if you dare take the night off, even in an act of purely pragmatic self-care.

Whether it’s with a disability, a child or a demanding second job (that actually pays the bills), artists must rigorously organise their lives in order to juggle the professional, the social and the exhaustibitional. Sometimes even thinking about exhaustion is, ironically, exhausting.

And on that note, we’re clocking out.

(1) Michelle Hamer, taken from email interview with Katie Paine

(2) http://performing.artshub.com.au/news-article/career-advice/performing-a...

_1-itok=q7TVq2G6.jpg)